Clients want to improve: This is one of several central treatment assumptions in DBT and not one that is widely accepted or believed in general mental health settings. When I present the DBT assumptions in my clinical trainings, it is inevitable for some clinicians to question the validity of this statement: “I don’t think all clients really want to get better” they tell me, or “If they really wanted to improve, wouldn’t they try harder?”

For as long as I have known, mental health institutions have smuggled in a haunting assumption, particularly when treatment responses are not favorable, that clients don’t really want to get better, that they “like” the sick role or “get too much out of” staying unwell. I have observed this both in my role as a psychologist and as an individual who has witnessed mental health approaches through the experience of family members since early childhood. The notion that a client does not want to improve is simultaneously laughable and deeply tragic. You can read my thoughts on the notion of “choice” in the face of neurobiology and environmental factors in my March 8th, 2023 blog post here: Is Recovery a Choice?

Clients want to improve.

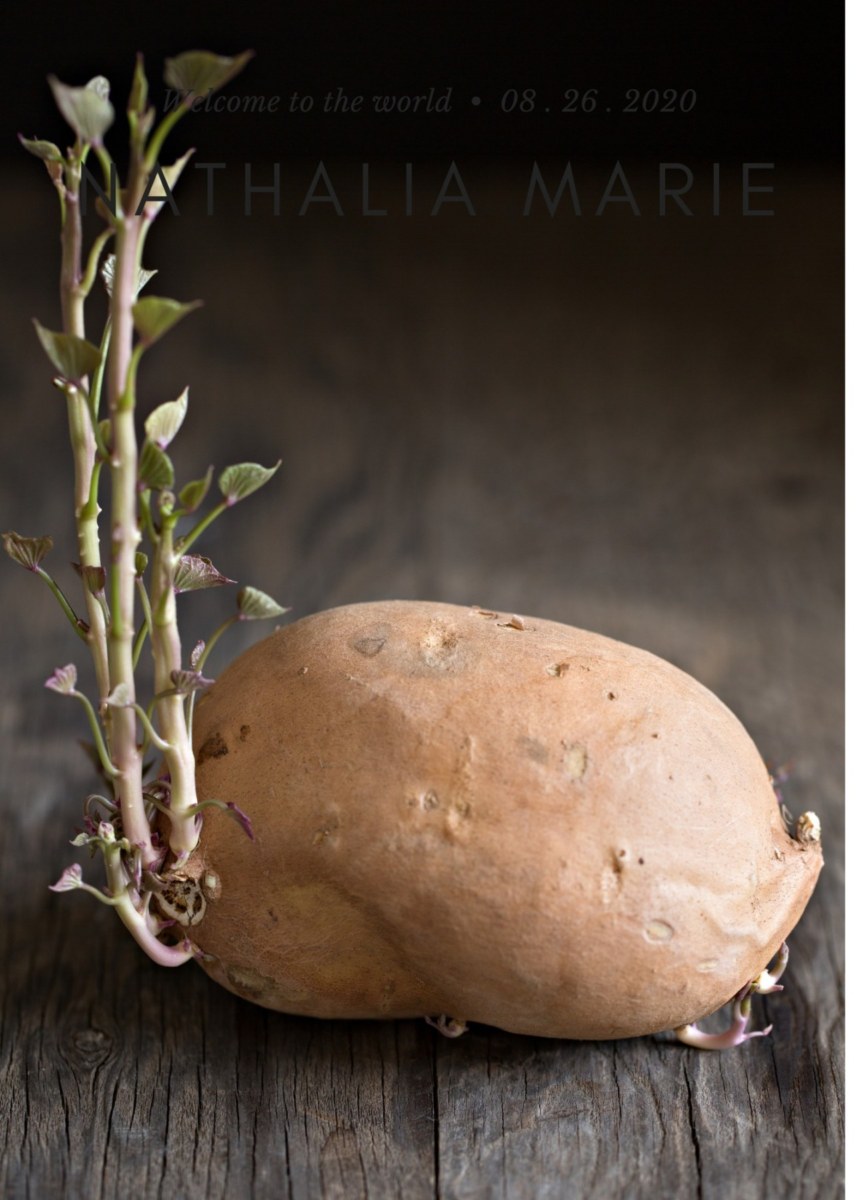

In graduate school, I studied the work of Carl Rogers, and wrote a long and meandering paper about his philosophical positions for a course I was taking at the time. I have kept that paper with me for over 25 years, packing it as I moved from city to city, and it currently maintains its place in a wooden box in my basement. I really should read that again. My point is that his view of human nature and change deeply resonated with me. Rogers was known for his work developing “client-centered” therapy. Many of his theories and musings have stayed with me over the years, like old tattoos that remind you of the things that hold great importance so you never forget them. One of his famous analogies was the “potato in the cellar” story. He spent his adolescence on the family farm and would later use his observations of farming and nature itself to contemplate human behaviour. He observed that the potatoes, which had been stored in the agriculturally hostile and unsuitable cellar, would, in fact, grow long, wobbly sprouts reaching tirelessly toward the small stream of light coming through the cellar window. In 1980, he wrote the following:

“The conditions were unfavourable but the potatoes would begin to sprout….a sort of desperate expression….under the most adverse circumstances, they were striving to become….so unfavourable have been the conditions in which people have developed that their lives often seem abnormal…yet the directional tendency in them can be trusted. The clue to understanding their behaviour is that they are striving, in the only ways that they perceive as available to them, to move toward growth, toward becoming. To others, the results may seem bizarre and futile, but they are life’s desperate attempt to become itself.”

Then, 1993, Marsha Linehan would publish her seminal and highly influential book on treating people with borderline personality disorder. One of the assumptions she expects DBT providers to make is that every client wants to improve. Just like the potatoes in the cellar. Linehan saw that her clients, the ones who were labelled “treatment resistant” and “manipulative”, wanted desperately to get better. This misunderstanding of the client’s attempts to solve their problems caused providers to reject and judge them, to effectively give up on them. They missed that their clients were desperately striving to get out of suffering, to grow, to find purpose, meaning, safety, and to make their way toward the light in whatever way their biology and learning histories allowed.

“The directional tendency can be trusted.”

The moment the clinician or the team or the system views people as not wanting to get better, the whole story changes. The entire approach hinges on whether or not one believes that people want to improve, whether the clinician trusts in the client’s inherent growth tendency. It is also extremely important not to confuse what reinforces a behaviour (e.g., feeling safe when admitted to hospital) for the impetus of the action itself (e.g., to survive, to self-regulate, to improve). Now, Rogers also believed that clients had everything within them to make changes and improve. In my experience, however, people often don’t have the skills, confidence, and support needed which is what led me to DBT, an approach in which I can balance both the deep belief that my clients want to improve and the need for them to learn new ways to strive toward that light.

I never forgot about those potatoes in the cellar, struggling and fighting vigorously to obtain something. Such an important way to think about human behaviour, to observe the instinctual tendency to grow even in the most unfavorable conditions.